Researched Papers: Using Quotations Effectively

If your college instructor wants you to cite every fact or opinion you find in an outside source, how do you make room for your own opinion?

- Paraphrase. You can introduce studies that agree with you (Smith 123; Jones and Chin 123) and those that disagree with you (Mohan and Corbett 200) without interrupting your own argument. (Note how efficiently I did that -- the parenthetical citations are designed to preserve the flow of ideas in the sentences that refer to outside ideas.)

- Quote Selectively. If you must use the original author's language, work a few words from the outside source into a sentence you wrote yourself. (If you can't supply at least as many words of your own analysis of and rebuttal to the quoted passage, then you are probably padding.)

- Avoid Summary. If you must quote several lines of another author's language, don't interrupt the flow of your own argument in order to summarize the material you have just quoted. (Generally speaking, summarizing someone else's ideas is one of the easiest ways to churn out words; while students often turn to summary when they want to boost their word count, paragraphs that merely summarize are not as intellectually engaging, and therefore not worth as many points, as paragraphs that analyze, synthesize, and evaluate. See "Writing that Demonstrates Thinking Ability.")

If you've already found good academic sources (including peer-reviewed journals) for your college research paper, you've got a good thesis and you've begun drafting your college research paper, this document will help you make your paper sound like a coherent argument, rather than a bunch of paragraphs strung together from other sources.

Note: laboriously rewriting source material so that it doesn't use any of the original words is pointless effort; even if you completely rewrite the original, you still need to cite the original author (except, of course, when the information is common knowledge).

Avoid long quotes. If your 10-page paper offers 6 or 8 long chunks taken from other sources, stitched together with sentences like, "This quote shows the idea that...", then you are not demonstrating the ability to write at the college level. Borrow shorter passages, even single words; integrate those passages into your own original argument.

Use quotes to launch discussion, not silence it. There's nothing actually wrong with ending a paragraph, section, or paper with a quotation. But if you have a habit of asking a bunch of random questions, poking around the issue, and then "proving" your point by finishing up with a quotation, as if there is nothing more to say about the topic now that you've presented your quote, then you're not demonstrating the ability to engage critically with a complex problem that might have numerous plausible solutions. You may instead be trying to discourage your reader from questioning your claims.

Include quotes from sources that disagree with your thesis. Rather than silencing an alternate or opposing claim, aim to show your reader how a careful consideration of all the evidence -- both for and against -- leads a reasonable skeptic to agree with your perspective.

Avoid encapsulated, serial summaries of your outside sources. Your high school teachers may have rewarded you for writing good summaries. But a college paper requires you to think on a much more advanced level than a string of paragraphs, each of which summarizes a separate outside source.

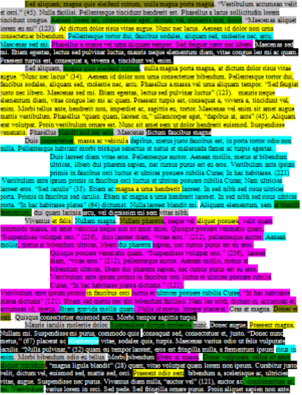

Avoid writing a separate paragraph on each of your sources. In the image on the right, we see a typical five-paragraph paper, with a one-paragraph introduction, a one-paragraph conclusion, and three supporting paragraphs. The student has found three good sources, but unfortunately, the student has chosen to devote one paragraph to each source. That kind of layout presumes that your job as an academic is to summarize what other people have written. In truth, your job as an academic writer is to demonstrate your ability to create new links between materials that have already been published. You can't do that if you treat your sources one at a time, in self-contained paragraphs. |

|

In the following revision, we still have a five-paragraph paper, but notice that the first paragraph first introduces a main idea (represented here in dark green), then briefly introduces all three supporting ideas (represented by a full sentence devoted to the yellow, blue, and magenta ideas).

The first supporting paragraph, which presents the yellow idea, begins by restating the main idea. (Don't use the exact same words of course; see thesis reminders.) Note that the blue paragraph begins by referring to the relationship between the main idea and the first supporting point. We see a reference to the yellow point in the middle of the blue paragraph, and the blue paragraph winds up by repeating the main idea and also offering a conclusion (here represented by white text on a black background). The magenta paragraph begins by restating the relationship between the yellow and blue ideas, and refers briefly to both of these earlier points as it develops the magenta idea. Note that the final paragraph does not merely restate the contents of the yellow, blue, and magenta paragraphs; instead, it refers briefly to the relationship between those supporting points and the main idea, but spends more time addressing the main idea. |

|

Avoid a rigid, simplistic organizational structure focused only on the

sources you have found.

|

|

| This structure won't permit you to make original connections between your sources and your main idea. You will end up writing too much summary and not enough original argument. The organization of your paper should flow from the argument that you plan to make. Consider the following: | |

|

|

Note that the revised outline deals with each source in more than one paragraph, and due to the complexity of Point 2, the author devotes two paragraphs to it. This student might need to do additional research. Perhaps source D only appears to support claims made in one section, and perhaps source E only exists to support a minor claim made about source B. If a source is not that important to your argument, but it helps you make one small point, then refer to the source where you need to and forget about it. |

|

If you ask yourself questions about how your sources relate to one another, then you can avoid summary and still have plenty to write about.

- What if source A is the only evidence in favor of point 3, while

B and C oppose it. Source D doesn't mention this point at all.

- Is that a weakness in D's argument?

- A sign that D isn't a reliable source?

- Or is that point simply outside the scope of the argument D was trying to make?

- Did some authors have access to information that the author of D

did now know about?

- Maybe source D was published early, and new information has come to light since then. Is source D now irrelevant, or did the author raise good questions that are worth re-considering now that there is additional evidence?

- Maybe source D was only looking at a problem in America, while the other sources also included Canada and Europe. Should you respond by narrowing or broadening your focus?

These are subtleties that you cannot really investigate when you introduce outside sources only in self-contained paragraphs that reference no other sources.

MLA Parenthetical Citations

The MLA-style in-text citation involves just the author's last name, a space (not a comma), and then the page number (or line number, for verse).

| One engineer who figures prominently in all accounts of the 1986 Challenger accident says NASA was "absolutely relentless and Machiavellian" about following procedures to the letter (Vaughan 221). |

Any college writing handbook will have multiple examples of how to cite multiple pages from the same source, multiple works from the same author, and other variations. But the main point is that you should leave the details for the Works Cited list.

Integrate Quotations from Outside Sources

Don't interrupt the flow of your own argument to give the author's full name or the source's full title. Spend fewer words introducing your sources, and devote more words to expressing and developing your own ideas in ways that use shorter quotations, or even just a few words, from your outside sources.

Avoid clunky, high-schoolish documentation like the following:

| In the book Gramophone, Film, Typewriter, by Fredrich A. Kittler, it talks about writing and gender, and says on page 186, "an omnipresent metaphor equated women with the white sheet of nature or virginity onto which a very male stylus could inscribe the glory of its authorship." As you can see from this quote, all this would change when women started working as professional typists. | |

| The passages "it talks about"

and "As you can see from this quote" are very

weak attempts to engage with the ideas presented by Kittler.

In addition, "In the book... it talks" is ungrammatical

("the book" and "it" are redundant

subjects) and nonsensical (books don't talk). |

|

| In the mid 1880s, "an omnipresent metaphor equated women with the white sheet of nature or virginity onto which a very male stylus could inscribe the glory of its authorship" (Kittler 186), but all this would change when women started working as professional typists. | |

| This revision is marginally better, but only because it uses fewer words -- it's still not integrating the outside quote into the author's own argument. | |

Don't expend words writing about quotes and sources. If you use words like "in the book My Big Boring Academic Study, by Professor H. Pompous Windbag III, it says it says" or "the following quote by a government study shows that..." you are wasting words that would be better spent developing your ideas.

Using about the same space as the original, see how MLA style helps an author devote more words to developing the idea more fully. We shall continue to revise the above example:

| Before the invention of the typewriter, "an omnipresent metaphor" among professional writers concerned "a very male stylus" writing upon the passive, feminized "white sheet of nature or virginity" (Kittler 186). By contrast, the word "typewriter" referred to the machine as well as the female typist who used it (183). | |

| This revision is perhaps a bit hard to follow, when

taken out of context. But if you put a bit of introduction

into the space you saved by cutting back on wasted words,

the thought is clearer. |

|

| To Kittler, the concept of the pen as a masculine symbol imposing form and order upon feminized, virginal paper was "an omnipresent metaphor" (186) in the days before the typewriter. But businesses were soon clamoring for the services of typists, who were mostly female. In fact, "typewriter" meant both the machine and the woman who used it (183). | |

| The above revision mentions Kittler's name in the body, and cites two different places in Kittler's text (identified by page number alone). This is a perfectly acceptable variation of the standard author-page parenthetical citation. | |

While MLA Style generally expects authors to save details for the Works Cited pages, there's nothing wrong with introducing the work more fully -- if you have a good reason to do so. (See "Quotations: Integrating them in MLA Style.")

Dennis G. Jerz

01 Nov 2001 -- draft posted

03 Oct 2007 -- revisions

| Related Links |

Dennis G. Jerz Dennis G. Jerz Dennis G. Jerz David Nies and Dennis G. Jerz

Dennis G. Jerz |