My undergraduates are working their way through N. Katherine Hayle’s My Mother Was a Computer. They told me that they benefitted from the notes I wrote the other day, so I’m continuing the effort.

In Chapter 3, Hayles reminds us that the “worldviews of speech, writing, and code” are not merely theories, they are observable phenomena in the material world, with economic and sensory physical properties. All media are constrained, and the constraints built into each medium define the way artifacts are constructed in, and genres develop within, that medium.

In keeping with her earlier assertion that a complete understanding of digital text cannot happen unless we explore how we perceive them with our physical bodies, Hayles reminds us that print culture also involves variation, deviation, imperfect copying, and variable interpretation, the “dream of information” centers around the idea that texts that can be distributed electronically change the economy of information.

The Bibles of medieval Europe, which were so lavishly illustrated that, if you consider the hours of labor that went into their construction, the Bible may be more valuable than the church in which it was kept. In age when information was hard to get, when reading was a rare skill, when it resided in one physical place, and when the act of copying the information took considerable effort, information was valuable because it was scarce. The “dream of information” centers on the liberation that comes when information is not scarce, when the value in a network is not the isolated chunks of information but the power of the network to distribute that information. (She contrasts this with the “regime of scarcity.”

Hayles’s exploration of the human response to code (and artifacts created by that code) begins with an analysis of literary depictions of bodies, as those bodies interact with code. While she duly notes the value that comes from the free exchange of information, she also notes the darker side. If scarcity has no meaning, and a society can create whatever it needs or desires (whether by conjuring up digital copies or fabricating items molecularly), then “private property would cease to be meaningful,” and — at least as many dystopian science fiction writers see it — the erosion of the concept of “ownership” will spread to the personal routines that govern our interaction with a commodified world (c.f. Google’s Project Glass video… who would benefit from knowing exactly what we are looking at, all day long?) If we no longer own our daily routines, our social relationships, and even our thoughts, then ownership of the bodies that interact with the digital world also becomes suspect, as corporations will access the digital stream to sell us the products that will nourish, tan, heal, enhance, modify, calm, protect, and otherwise interact with our bodies.

In order to explore how existing power structures may use “code” in the information economy, Hayles considers three works of fiction. While we cannot sensibly say that, because an imaginary character in a fictional world performs action X, or expresses reaction Y, that we can therefore “prove” something about our world, we can at least examine how imaginary depictions of exaggerated, intensified, or impossible situations expose us to categories, ideas, and possibilities that we can draw on in order to formulate questions to ask of our own experiences.

Henry James, “In the Cage”

Project Gutenberg (full e-text) | Wikipedia

The nameless protagonist is young female telegraph operator — people pay her a fee, submit a hand-written note, which she mentally translates into Morse code; likewise, she receives Morse code messages, and translates them back to English. This was one of the few jobs in which a working woman could come into regular contact with men and women of a wide range of classes, an expansive possibility that James emphasizes through contrast — the telegraph operator’s decoding goes beyond Morse code, so that she decodes the secret messages of a pair of aristocratic lovers, inserting herself into a romance enabled by the telegraph, while she herself occupies a very confined workplace — in a cage, which echoes her own limited social status.

Captain Everard and Lady Bradeen have been sending coded messages to each other as part of an illicit love affair, and our protagonist, while going about her routine job of translating English into Morse code, has figured out, or seems to think she has figured out, the pseudonyms the lovers are using, to the extent that she takes it upon herself to change one of the message she sends, thinking she has caught a mistake. This change that she inserted into the code may or may not have resulted in one of the messages being misdelivered, an action that threatens Captain Everard.

Though her status is so lowly that she cannot possibly be a threat to this relationship, she inserts herself into the relationship further by arranging an accidental-on-purpose meeting with the captain, and while she considers blackmail, and seems also to consider prostitution (at least briefly), she settles for telling him (from memory) the contents of the missing telegram.

The information itself is not that important; this is the telegram that the protagonist edited, and the text she recalls for the captain is some sort of code; James doesn’t explain all this in great detail, because the story actually focuses on the protagonist’s class ambitions, her own desire to keep a job where she can at least participate in high society vicariously by translating their telegrams, and thus keep alive the dream that her access to information will somehow benefit her marriage prospects. (She does have a working-class suitor, but she has higher hopes.)

Hayles notes that the miscommunication that leads to the climax is not a problem of ambiguous phrasing, but rather a coding error; either the lovers made a mistake with their code, or the telegraph operator made a mistake when she changed that code, or the telegraph operator made a mistake when she contacted the Captain to correct the previous error; however you take it, what Hayles calls the “passive code” of the telegraph has a direct impact on the bodies of the aristocrats involved in the love affair (Lord Bradeen accuses Lady Bradeen of stealing something to give to the debt-ridden Captain as a gift, but the telegraph operator recognizes that this object was probably the telegram — perhaps even more damning because it is encoded infidelity, rather than a material possession like money.) The protagonist, who is a cipher because she herself is never named, has no physical participation in the love affair, though her involvement (by changing the code, then sharing what she remembers about the coded message) gives her power over how that relationship progresses.

Philip K. Dick: The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch

This work is a novel-length study in alternate consciousness, which in the 1960s (when this story was published) was most closely associated with mind-altering drugs. The story describes colonists on Mars, working pretty much as slaves for Earth’s wealthy; the colonists attempt to escape their horrible daily lives through a drug (“Can-D”) that enables them to project their consciousness inside dolls that exist in an idyllic world. If you can imagine The Sims, but all male players inhabited a single male avatar, and all female players inhabited a single female avatar, and the actions of the avatar were determined by the majority of the wishes of all players of that avatar, you’d have some idea of the scenario.

“Can-D” and the products for the doll world are carefully deployed to keep the Martian colonists under control. A corporate rival introduces “Chew-Z,” which presents a different kind of drug-induced alternate world, one that changes the perception of time (a few seconds in the Chew-Z hallucination can seem like hours or months), though this world is controlled not by the communal will of its participants, but rather by the inventor of Chew-Z, who intends to use the drug to gain control over everyone on both Mars and Earth.

Some of the tropes in this story, such as “if you die in the dream world, you die in real life,” or “it was all a dream… or was it?” will seem very familiar to anyone who has watched a “Holodeck” episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation, but this was years before even the most primitive version of the Internet existed, so this very creative depiction of two very different kinds of virtual worlds (one in which users share control, one in which the owner has all control) do give us some useful insights in to what happens when corporations assert ownership over our imagination, and when we become addicted to the kinds of imagination that can only be enabled by products owned by others, who claim ownership and control over the worlds we create with those tools. (This is important, when we consider how difficult Facebook makes it for us to extract the content we put into Facebook.)

As other characters resolve to fight the inventor of the dangerous Chew-Z variant of simulated life, we learn that Chew-Z is in fact part of an alien plot to take over the world, and the alien mastermined is so charmed by the simple life on Mars that it plans to take over the real-world body of one of the Martian colonists — a life the the alien prefers to the simulation it is promoting for everyone else.

Tiptree, “The Girl Who Plugged In”

Seton Hill’s theater department performed a one-act play version of this a few years ago.

P[hiladelphia] Burke is a bag lady, living on the fringe of a near-future society in which advertising is illegal, so corporations wishing to publicize products have do depend on celebrity endorsements. Just as Disney realized that, instead of paying established Hollywood stars to be in their movies, it was cheaper to use The Disney Channel to create stars (Britney Spears, Miley Cyrus, etc.), in Tiptree’s utopia, the corporation GTX genetically engineers a beautiful woman without a brain, and contrast with P. Burke to virtually inhabit the beautiful body. Burke’s emotions, which are sincere because she has lived a genuinely harsh life, provide the secret sauce that makes “Delphi” a superstar. Burke, who in reality is deformed, perceives Delphi’s body as her own; she has to unplug from Delphi every so often in order to tend to her own real-world body, which involves eating, excreting, etc., during which time Delphi seems to sleep; when Burke is plugged into Delphi, Burke’s body sleeps.

The story follows the lab technician who gets to know the real P. Burke, and Paul, the son of the GTX mogul, who falls in love with Delphi. Complications ensue when Paul learns that something is controlling Delphi remotely, and mistaking the transmissions as an attack on the “real” Delphi, first tries to cut Delphi off from the source, and then heads directly to the source of the transmissions, when he confronts P. Burke, whose real name “Philadelphia” contains the entity “Delphi,” and whose soul inside Delphi’s body made Delphi what she is. The confrontation leads to tragic results, with some hint that at least part of Burke’s soul lives on in Delphi, who shows some signs of independent thought even after Burke’s death. But Tiptree ups the ante on us by having an underling in GTX invent time travel, which inscribes the rise of the corporation as the inevitable end result, regardless of the status of the star-crossed lovers.

The Seton Hill theater department produced “The Girl Who Was Plugged In” as a one-act play a few years ago.

I also found this Sci-Fi Channel version.

Summation

Hayles examines all three stories through a gendered, embodied lens; by which I mean she explores “the restricted ways in which the female characters can engage in commerce” in information-dominated environments.

If we continue to read speculative literature, we prepare ourselves to recognize emerging patterns in our own world, since these patterns have been right before our eyes, in the form of fiction, for decades.

For Hayles, “Despite the differences in historical contexts and authorial voices the give these fictions distinctive visions, they concur in puncturing the dream of an informational realm that can escape the constraints of scarcity.”

Translation and Values in New Media

In Chapter 4, Hayles focuses on the issue of translation. When a printed book is converted into an etext, some things are gained, but others are lost. What counts as a “gain” and a “loss” depends on value judgments, and Hayles points out that much of the thinking surrounding etexts is “shot through with assumptions specific to print.” She sees an opportunity to “reformulate fundamental ideas about texts and, in the process, to see print as well as electronic texts with fresh eyes.”

The William Blake archive is an early example of meticulous digital scholarship, demonstrating what knew knowledge we can generate about existing texts when we access the power of computers.

Blake was a poet who lived in the late 18th and early 19th century; he is known for Romantic poetry (a term which, to literary scholars, does not mean “lovey dovey mush” but rather poetry that focuses on the passions, in some ways a rejection of the industrial revolution, against the aristocracy, against the effort to tame and manage and measure nature and human potential. Yes, romantic love was a subject of romantic poetry, but so too would be a celebration of nature, of human potential, a longing for the divine, a rejection of the routine.

Blake was unusual because he was also a printer and an artist. He hand-painted many of his works, and his images were as influential as his words. Serious Blake scholars say you can’t really understand the words without the images, or vice-versa… however, since he hand-painted many of his works, no two are the same.

The William Blake Archive opened in 1996, two years before Google.com went live, 10 years before Facebook was opened up to the public.

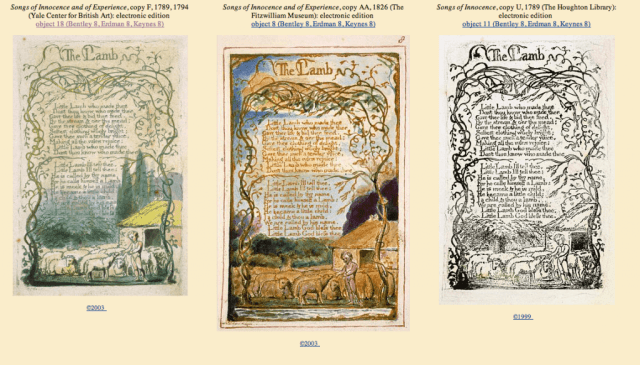

The Blake Archive aims to scan in and make available for study every known variant copy of Blake’s work, with detailed information on where each physical copy is located, who owns it, whether the text is complete, etc. Here are three different versions of “The Lamb.”

Undergraduates usually encounter literary texts in the form of anthologies that have been carefully vetted by experts. But in the rough and tumble world of literary bibliography, the idea of one “correct” text is a myth. People at all stages of the process, from author to editor to printer to book owner, make changes. Words are inserted, pages removed, inserts pasted in, titles are added or removed or swapped.

If an author writes a rough, passionate poem as a young man, which earns him a reputation, then after decades of living on that reputation he republishes the poem in a collection, but makes some edits to improve the poem, which version of the poem is the “real” one?

With access to a resource like the Blake Archive, scholars don’t have to depend on letting someone else make that decision for them.

If there’s one lesson I hope my advanced new media students learn, it’s that thinking of coding as somebody else’s job is throwing up your hands and giving power away to the corporations who will limit your choices for the sake of efficiency, who will deny you ownership of your own data, your own privacy, your own thoughts, unless you take active steps to protect that privacy.

No sane publisher would print a book with hundreds of copies of the same page, just so that a bunch of obsessed Blake experts could study the differences. But Blake scholars, who knew enough about Blake to value the insights they could draw from such a comparison, saw that print publishers saw little chance of making money, so the scholars invented an online resource that would be impossible in the print world. It’s a massive project, and humanities scholars are right to hold it up as a towering achievement.

Hayles has a critique of this project.

The website collects meticulous details about how differences in printing processes, coloration, and paper quality affect the reader’s encounter with the artifact. However, “Concentrating on how the material differences of print texts affect meaning, as does the William Blake Archive, dislike feeling slight texture differences on an elephant’s tail while ignoring the ways in which the tail differs from the rest of the elephant.”

In other words, the different ways in which researchers experience the William Blake Archives (on computers with different resolutions, on internet connections of different speeds, in situations when data access costs different amounts of money, for classrooms where students have different levels of access to the internet) are themselves of great interest, and the WB Archive seems, at least as Hayles sees it, to undervalue those sorts of questions.

Hayles takes a few steps back to introduce bibliographic terms.

The “work” is an abstract entity… we refer to Shakespeare’s Hamlet, even though we can’t actually hold the “work” — we have to hold a “text.” Thus, a “text” of Hamlet might be a hand-written Elizabethan parchment, or a handsome 18-century volume intended for private study, or a cheap paperback in a student’s backpack. But what scholars consider the full-length Hamlet would take about 4 hours to perform… modern productions tend to chop that down to three hours or less. Your “version” of Hamlet might be very different from mine, regardless of the physical form it takes.

Hayles notes that these categories, which were created for print texts, are limited when we refer to digital texts, especially when those digital texts take their form only when perceived by the human body that is perceiving it.

Hayles invokes Matt Kirschenbaum’s “call for the thorough rethinking of the ‘materiality of first generation objets’ in electronic media.”

In 2010, I was privileged to work with a group of scholars including Kirschenbaum, on a practical attempt to apply traditional print-era archival terms to a computer game.

Because each individual or subsequent encounter with the same interactive work can generate different outputs, the adequacy of traditional descriptive models applied by librarians to enable scholars’ access to textual materials needs to be carefully examined. From the scholar’s (or teacher’s) perspective, even mundane activities such as a textual citation or assigning students a particular passage to read become problematic. Moreover, even the simplest electronic “text” is in fact a composite of many different symbolic layers, from microscopic traces on physical storage media up through machine code, higher-level languages, and finally the visible characters one actually reads on a screen.

[..]

In the case of an electronic object, the complications proliferate almost exponentially [Renear 2006]. At first it might seem that all versions of ADVENTURE should be grouped under a single “Work,” a particular instance of the game (the last version modified by Don Woods, for instance) should be the “Expression,” a particular file with a unique MD5 hash should be the “Manifestation,” and an individual copy of that file (perhaps on a Commodore 64 664 Block disk) would be the “Item.” But what if the text read by the reader is exactly the same, but the underlying code is different? These variants might be simple (a comment added to the FORTRAN source code), peripheral (such as the ability to recognize “x” as a synonym for the command “examine”), or very large (a port of the code from FORTRAN to BASIC). Should these code level variants be considered different expressions? To further complicate matters, what if the FORTRAN code were exactly the same but compiled to two different chips? For example, an IBM mainframe and a Commodore 64 might both have a FORTRAN compiler, but the two compilers will interpret the FORTRAN to a different set of machine instructions. It might also be the case that two FORTRAN compilers designed by different programmers will generate slightly different machine language. Even the same compiler might generate slightly different machine code from a single source code file depending on the options with which it is invoked. Should these compiled executables, different in their binary structure but based on the same FORTRAN code, represent different “Manifestations” or different “Expressions”? —Twisty Little Passages Almost All Alike: Applying the FRBR Model to a Classic Computer Game

Owing to the economic and physical properties of a book, print publishers have long held that the reason we study two different versions of the same text is to determine which one is the “error” and which one is “correct.” But we can learn a lot by watching a text as it evolves; editorial attempts to authorize one variation and silence another close off the kind of intellectual inquiry that benefits from having multiple versions.

McGann (a driving force behind the William Blake Archives, and, coincidentally, my undergraduate adviser when I was an undergrad at the University of Virginia) asks what would happen if we “abandon the movement towards convergence and … try instead to liberate the multiplicities of texts through a series of deformation” (Hayles).

Hayles praises McGann for his interest in, for example, using Photoshop to tweak and adjust and distort Blake’s images, in order to learn something about the images that we couldn’t learn with the naked eye, rather than limiting the computer to a tool that duplicates the printed page.

I roll my eyes every time I open the USA Today app on my iPad, and see the ragged simulated paper edge at the top of the screen.

I roll my eyes every time I open the USA Today app on my iPad, and see the ragged simulated paper edge at the top of the screen.

Hayles feels that McGann errs when he compares hypertext authors with literary classics and finds the hypertext authors wanting. While she seems to agree in principle that it’s fair to say Italo Calvino writes better novels than Stuart Moulthrop writes hypertext, she complains that a modern novel is the result of 500 years of bibliographic, literary, and cultural history; it would be more fair to compare a contemporary hypertext with the books that were being published 15 years after the printing press came to Europe.

Reading any complex text is a process.

Let’s consider this poem.

I never liked the World Trade Center.

When it went up I talked it down

As did many other New Yorkers.

The twin towers were ugly monoliths

That lacked the details the ornament the character (5)

Of the Empire State Building and especially

The Chrysler Building, everyone’s favorite,

With its scalloped top, so noble.

The World Trade Center was an example of what was wrong

With American architecture, (10)

And it stayed that way for twenty-five years

Until that Friday afternoon in February

When the bomb went off and the buildings became

A great symbol of America, like the Statue

Of Liberty at the end of Hitchcock’s Saboteur. (15)

My whole attitude toward the World Trade Center

Changed overnight. I began to like the way

It comes into view as you reach Sixth Avenue

From any side street, the way the tops

Of the towers dissolve into white skies (20)

In the east when you cross the Hudson

Into the city across the George Washington Bridge.

The title alone was probably enough to get you to form some initial emotional response to this poem.

But let me direct your attention to a few points that might help you to construct a different response.

The past tense “”The twin towers were ugly monoliths” (4) make sense, but what about the present tense “I began to like the way / It comes into view as you reach Sixth Avenue” (18)?

What about “Until that Friday afternoon in February / When the bomb went off” (12)?

Would it help if I pointed out I copied this text from this page, “World Trade Center: Literary and Cultural Reflections,” that I put together the afternoon of Sept 11, 2001, while I was sitting at my desk trying to come to terms with the tragedy?

The poem was written in 1996, responding to in incident from 1993 — a truck bomb exploded in the parking garage, killing six people, but leaving the World Trade Center itself unscathed. The poet describes how the attack made him fall in love with the target.

The poem, which had one meaning when it was published in 1996, acquired a completely different meaning when I read it on 9.11.2001.

Now let’s consider a different text. If we want to study this, what kinds of variations will we see? What kinds of variations are significant, and what kinds will have a serious impact on our ability to interpret the experience?

Hayles identifies an electronic text as a “distrubted phenomenon,” experienced in stages, accumulated by the contributions of data files, hardware, a power source, an interface, etc. “Omit any one of them, and the text literally cannot be produced. For this reason it would be more accurate to call an electronic text a process than an object.”

A bit later, “The materiality of an embodied text is the interaction of its physical characteristics with its signifying strategies…. Because materiality in this view is bound up with the text’s content, it cannot be specified in advance, as if it existed independent of content. Rather, it is an emergent property.”

Literary scholars don’t see the text as containing or communicating a single correct meaning; rather, they see a community of skilled readers coming to an agreement about what the text means.

But as we can see from the WTC poem, even the meaning of a static printed text fluctuates over time.

Hayles begins tying her insights back to the general theme of code, presenting machine translation as a fusion of code and linguistics. We can see, in this passage, her reminder that linguistic translation is a complex process, and that while it is possible for a translator to improve upon the original, the intellectual work of translating a medium from print to digital, or interpreting a digital work according to the criteria appropriate to the digital genre, is challenging intellectual work that calls for new categories of understanding, new layers of critical thinking, and new modes of writing.

But she also asks us not “not to overstate the fluidity of electronic texts compared to print,” since she notes that Borges (writing in a piece that is not the one we read) managed to raise the kinds of ideas we associate with fluid texts, even though he was writing for the print medium; she uses this observation to touch off a series of reflections on new media translation (including the assessment that Blake would have loved the computer … a sentiment she attributes to someone named “Van Lieshout” — what a name!)

Hayles winds up chapter 4: “Through the feedback loops in which electronic text recycles print and the programs generating electronic text recycle code, we glimpse the complex dynamics by which intermediation connects print and electronic text, language and code, “original” and translation, the specificities of particular instantiations and the endless novelty of recombination… We already know that language matters…. media and materiality also matter.”